How do you go about value investing?

“It is not about buying cheap stocks, but is buying good stocks cheap.”

Value investing is often mistaken for buying ‘cheap’ stocks. Therefore, you often simply look for a stock with a low PE ratio, or a low price to book value or with good dividend yield. These are easy ways to assess the relative value of a company. But value investing is not about buying companies that appear cheap based on these parameters. Value investing is a philosophy of buying a company at a price that is lower than its intrinsic value.

The philosophy of value investing has evolved over time from the quantitative parameters-based approach advocated by Benjamin Graham to the intrinsic value-based approach advocated by Warren Buffett. In a world where interest rates are near zero and majority of asset allocation is towards risky assets, the intrinsic value-based approach holds much relevance.

So, what’s intrinsic value all about? How does value investing fit in context of what markets look for? What causes valuation changes and what are the pitfalls in value investing that you need to avoid? We look at these, and many other, aspects in this article.

Accurately estimating intrinsic value

Let’s start with understanding intrinsic value, the cornerstone to value investing. A stock’s intrinsic value is the sum of the present value of all future cash flows. It can also be defined as the price that a rational investor is willing to pay for a stock. In other words, it is the “fair price” for a stock.

The method to determine intrinsic value is DCF or Discounted Cash Flow method. Estimating intrinsic value using DCF method involves correct estimation of following parameters:

- Growth rate

- Forecast period

- Free cash flows

- Terminal growth rate

- Discount rate (WACC)

Seems simple, doesn’t it? Just plug the numbers in, and voila! Not quite. The inputs listed above are estimates. Your intrinsic value calculation is as good as your estimates. In most DCF calculations, errors (or over-estimation and under-estimation) are likely to happen in assuming long term growth rate as well as the forecast period. This is because the long term period can have many moving variables concerning the company’s business, its industry scope and growth, economic scenario in the long term that can have many moving variables. Long forecasting periods also give rise to the problem of forecasting the discount rate (WACC) correctly.

And as a result, the DCF method is practically difficult to do and to arrive at right estimate of intrinsic value. Does that mean it’s a failed exercise? No. While it may be hard to accurately pin the intrinsic value, it certainly is possible to arrive at a ballpark figure – as put out by Warren Buffet himself.

Do remember that ballpark estimates still require significant understanding of:

- The growth cycle of the company you are looking at,

- The longevity of the high growth phase, if it is a growing company, or the stable rate of growth if it is mature

- The ability to forecast cash flows for longer period of time with reasonable accuracy

- The play between interest rates and costs of capital to arrive at discount rates to use, and how changes in interest rates can cause a spike or drop discount rates.

Therefore, short-cut methods using valuation ratios are popular. Investors normally use a combination of parameters such as Earnings Growth Rate, PE Ratio, Price to Book Value Ratio, Replacement Cost, and the EV/EBIDTA Ratio to assess whether a stock is trading at a fair price or not. Do remember that using such ratios is always a relative exercise. There are no hard-and-fast cut-offs on what is high or low. You will need to look at these ratios in light of historic levels, what levels peers in similar businesses are at, and where markets are – within the overall picture of where the company can go in terms of growth.

Whether it is using the DCF method to arrive at intrinsic value or a combination of ratios to assess the fair price of a stock, it is essential that you do this analysis to practice value investing.

What is value?

Myth: Value investing means buying stocks with a low PE or P/BV ratio or at high dividend yield.

Reality: A company that can grow its earnings at high growth rates for longer period of time qualifies for value investing even if the stock is trading at a PE ratio of 30 or 40 times, is 5 or 10 times its book value or at a 2% dividend yield. In other words – what value investing says is “buy stocks below intrinsic value”. It does not put a number to the PE P/BV ratio, nor does it suggest dividend yield as a key parameter.

To put it in perspective, in value investing, investors look to buy great businesses at reasonable valuation. This is what we hear from the practitioners of value investing, especially the Warren Buffett style. As he puts it – “It is far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than buying a fair company at a wonderful price”.

Here, there are two parts: one is qualitative (great business) and the other is quantitative (reasonable valuation). Let’s assume the qualitative aspect is met and the business as such is a sound one. Now, take the second part. You need to assess whether you can make returns at the prevailing stock price, using intrinsic value.

The method of estimating the intrinsic value can be any of the following:

- DCF or multi-stage DCF for steady/high growth companies

- Replacement cost for commodity companies at bottom of a cycle

- A combination of various ratios like PE ratio, Price to Book Value ratio or EV/EBIDTA ratio.

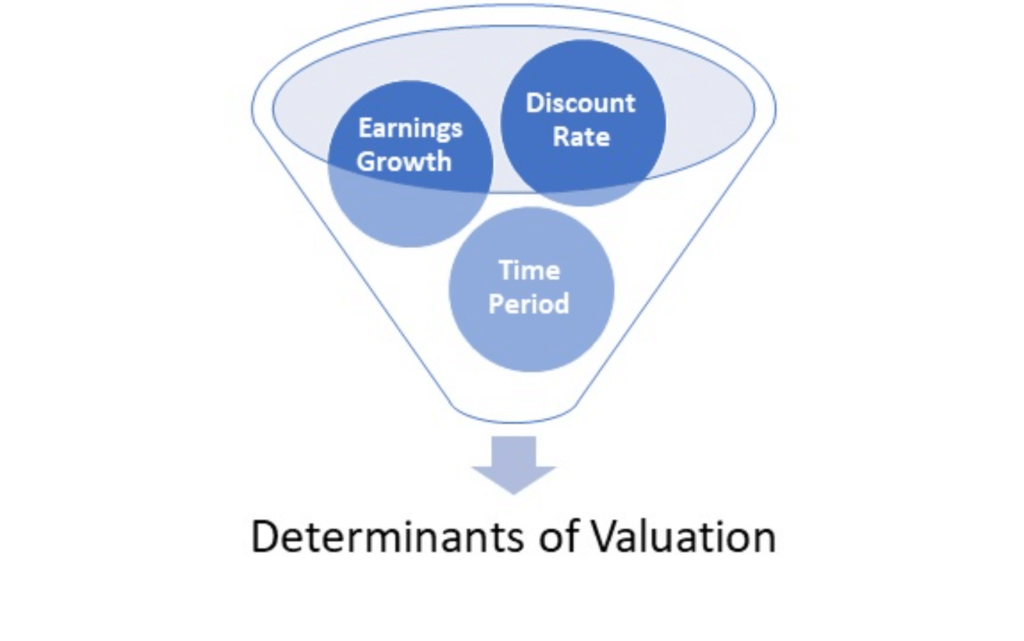

The key variables here are the growth rate, interest rate and the time horizon. Understanding the interplay between these variables will help put valuations in perspective. For a particular PE, the earnings growth and the interest rate scenario will help determine if it is a value buy or not. For example, when interest rates are high and market PEs can contract, you would need a company with a high growth rate and lower valuations to offer returns. But in a low interest rate scenario, even moderate growth can make valuations worthwhile.

Let’s see with an example of a high and low interest rate scenario.

High interest rate scenario

Here are the basic assumptions:

- Market PE of 25 at present is at or near its peak and interest rates are stable at 4%

- In a 10-year horizon, interest rates may rise and the market PE may stay put or contract

- Equity risk premium is 5%

Now, consider the table below.

As you can see, in a high interest rate scenario with PE contractions, you need a high growth rate and lower valuations if you are to derive meaningful returns

Falling interest rate scenario

Here are the basic assumptions:

- Market PE can rise further to 33 as interest rates fall to 3%, low risk of PE contracting.

- Equity risk premium of 5% for India

As you can see, low interest rate scenarios give more room for slower growth. Companies with moderate growth can turn out to be reasonable investments even at higher PE multiples.

Market sentiment and value investing

In stock markets human emotions plays a big role. Behavioral biases may lead to concentration of capital in certain stocks and sectors. In our market history, these behavioral biases have led to euphoria in various sectors at different periods like the IT Sector in 2001, the infrastructure and real estate sector in 2008, mid-caps in 2017, the NBFC sector in 2018, and the quality stocks in 2020. Valuations in these sectors went to astronomical levels. In each of these sectors, the key ratios like PE ratio or Price to Book Value Ratio or EV/EBIDTA ratios have significantly exceeded acceptable levels.

Those following value investing were often criticized for avoiding such stocks or sectors when they were hot, even as their returns took a beating. But when there is significant valuation premium built into stocks, especially due to behavioural biases, value investing by essence would mean passing over such stocks.

Therefore, looking at out-of-favour sectors can help spot value opportunities. There are a few ways you can do so:

- Running stock screeners using filters such as earnings and revenue growth, ROE, and valuations.

- Looking at sector indices and how they have performed against the Nifty 50 or the Sensex. Sectors that are lagging behind the benchmark market indices are usually those that are out of favour.

- Looking at valuation trends in stocks or sector indices.

What you’re looking for are stocks trading at discount to their valuation. Behavioral biases like risk aversion or loss aversion keep investors away from such stocks. When the trend reverses, value investors stand to gain significantly.

S Naren, CIO at ICICI Prudential AMC and a firm proponent of value-style investing, declared in a 2014 Morning Star investor conference that he looks for factors such as fear, lack of flows, past returns, and valuations in his value investing framework.

Factors affecting valuations

Apart from stock-market whimsies, what affects a stock’s valuation? Here are some of the more important ones:

Economic Cycles: A large part of banking stocks moved from growth to de-growth following the downturn in the economic cycle post 2011. Many of them turned out to be “value traps” and the sector went through severe pain for about a decade. But then, the sector went through consolidation and re-capitalisation, and made a strong come back from the cyclical downturn in the way it should be - fewer players with size and scale.

Business Cycles: In India, IT services sector is known for great value creation to shareholders. If we take top 15 companies by marketcap, 4 are IT services companies. From being a high growth sector, the nature changed to that of low growth in the years post 2015. Again, a transformative period injected new life into the sector, which regained its mojo recently. Stocks were breaking out higher above their 10-year PE ratio band.

Commodity Cycles: Commodity stocks are a highly cyclical category and the cycles take valuations to extremes. In India, we have seen several large companies taken to NCLT at the bottom of the cycle. Commodity stocks have also gone through consolidation with debt-ridden companies bought out by the stronger players, which served the latter’s expansion plans. In the commodity stocks, replacement cost provides the best estimate of their intrinsic value at the bottom of cycle and EV/EBIDTA ratio in the up-cycle. It is also important to check production capacities during the up-cycle post consolidation as stocks may do well beyond the expectation of investors. They might be having capacities significantly higher than in previous cycle.

Interest rate cycles: It is the key factor in determination of intrinsic value. Valuations move up or down based on the interest rate scenario. In markets like ours where there is huge flow of FPI money, global interest rates will also affect stock market valuations. In the last decade, post GFC and resultant weakening of capex cycle in economies, money has flowed to steady growing companies pushing their PE multiples significantly higher. The PE of Nifty 50 index has also moved up consistently over the last 5 years with lowering of interest rates. See the section above to know how interest rates can affect valuations.

Market Cycles: Economic up-cycle drives broad based rally in stocks whereas a distressed economy leads to concentration of capital into few stocks. This phase will be marked by lower reinvestment and demise of weaker companies. Investors also shift to large companies over a period as human behavioral biases come into play. As economic cycle turns up the stock market rally becomes broad based, companies will start to re-invest, competition will emerge, there will be new public issues until the cycle peaks out again.

One or more of the above factors will help buy into sectors and stocks at time when sentiment is low and valuations reasonable – the essence of value investing.

The growth vs value debate

The question below was posed by a participant in a 2014 panel discussion comprising investing legends Bharat Shah, S Narein, Kenneth Andrade, and the late Parag Parikh.

“What will a practitioner of “Value Investing” do when a stock moves from value stock to a growth stock?”

This question is an example on the misunderstanding that exists in the concept of “value investing”. The panelists advocated only one thing - value investing is about buying stocks below their intrinsic value. Bharat Shah put this distinction as something “artificial”. Kenneth Andrade’s take was that he is concerned about the purchase price in any investment he makes.

In reality, when the growth rate of a company changes (increases), its intrinsic value increases. That means it still exists within the value investing framework. A value investor gets concerned only when the market price deviates significantly from its intrinsic value (in their estimation). They will then shift from these stocks and into those where valuations are now below intrinsic value. As a result, their portfolios often comprise of stocks that look low/ relatively low on valuations; this sometimes gets mistaken for buying cheap stocks. According to practitioners of value investing, if there is anything that exists beyond it, that it is the ‘greater fool theory’ – but that’s a different debate!

Intrinsic value case studies

Below are two case studies on intrinsic value of two new age or high growth business using DCF and the insights based on it.

Case study 1: Prof. Aswath Damodaran’s valuation of Uber

Prof. Damodaran arrived at a valuation of $60 billion for Uber prior to its listing. The stock listed higher at $85 billion and journalists questioned where he fell short. His reply was that he was being highly optimistic to arrive at $60 billion valuation for a company that has lost billions of dollars until its way to IPO. This is where he makes the distinction between valuation and pricing.

The method Prof. Damodaran uses has been described in his book “Narratives and Numbers” where he shares his DCF and numbers of companies like Amazon, Uber, Tesla and Ferrari. It is a process of first telling the story (the narrative), check whether it is possible, plausible and probable and then convert the narrative into numbers.

Case study 2: Brokerage report on Avenue Supermarts

A recent brokerage report on Avenue Supermarts labelled the stock as a 100-bagger story over the next 25 years. The report made a long-range forecast of the company’s growth for 25 years with high growth rates. It built both a narrative and numbers by comparing it with Walmart. Again, though there were able to arrive at an intrinsic value for the stock using conventional methods, the accuracy of such long-range forecasts raises a question on accuracy or achievability of such valuations.

So, we can conclude that valuations of new age companies are arguably beyond the scope of value investing. The DCF method to find out intrinsic value has been very successful in the Warren Buffett style of investing in high-quality companies with wide economic moat, and so the longevity. But, in the above examples, it stretches the model and so, the achievability of the valuation is more open to change.

Therefore, narratives score over numbers for new age businesses. Those dedicated to value investing will have a tough time taking investing decisions, though Prof. Damodaran proved that such businesses can certainly be valued using DCF models.

Value investors - take the tough path

Don’t take the easy way of looking for stocks that have low PE or P/BV ratio or high in dividend yield. Instead, take companies that are growing at good growth rates or at steady rates. Try to dig into their numbers enough to arrive at their intrinsic value either using DCF or assess the fair price using a combination of PE ratio/Earnings yield, growth rate and interest rates.

Avoid sectors where the sentiment is too high for reasons we discussed earlier. If the estimated “intrinsic value” is less than the market price, wait for a correction to act. This will help understand and practice true value investing, and invest in companies that are growing at 1.5 to 2 times the nominal GDP growth rate.

Keep this golden rule in mind - value investing is not buying cheap stocks, but buying good stocks below fair price.